Wild West Podcast

Welcome to the Wild West podcast, where fact and legend merge. We present the true accounts of individuals who settled in towns built out of hunger for money, regulated by fast guns, who walked on both sides of the law, patrolling, investing in, and regulating the brothels, saloons, and gambling houses. These are stories of the men who made the history of the Old West come alive - bringing with them the birth of legends, brought to order by a six-gun and laid to rest with their boots on. Join us as we take you back in history to the legends of the Wild West. You can support our show by subscribing to Exclusive access to premium content at Wild West Podcast + https://www.buzzsprout.com/64094/subscribe or just buy us a cup of coffee at https://buymeacoffee.com/wildwestpodcast

Wild West Podcast

Fortifying the Frontier: Major General Dodge, Indian Diplomacy, and Life on the Western Kansas Plains

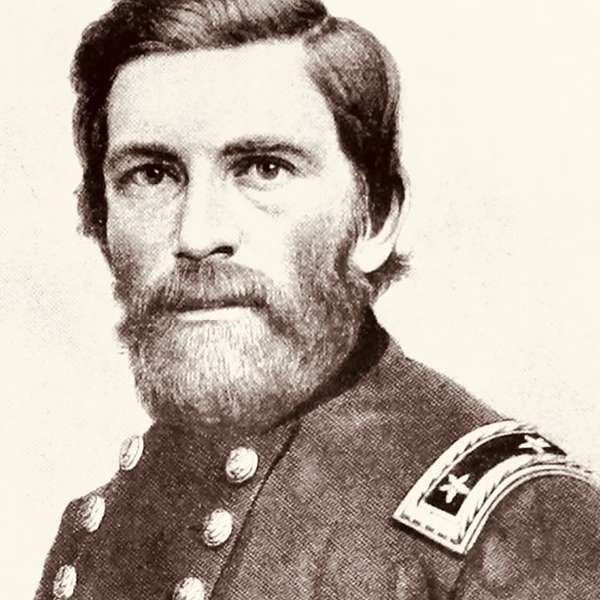

Step into the dusty boots of Major General Grenville Dodge as we venture into the heart of the post-Civil War American frontier, where securing the wild plains was as treacherous as it was vital. Our episode, guided by an esteemed historian, captures the essence of life at Fort Dodge, the strategic military stronghold pivotal in taming the Western Kansas frontier. Hear about the soldiers' grueling efforts to build safe havens amidst hostile territory, and how these fortifications laid the groundwork for a period of American history rife with conflict and transformation.

Witness the volatile relationship between the US military and the Plains Indian tribes through vivid tales of raids and the powerful leaders who orchestrated them. We unravel the complexities of Indian diplomacy with a spotlight on Kiowa Chief Satanta's influence, his storied battle gear, and the intense negotiations over captive settlers—a sobering reality faced by those like Mary Matthews, whose personal account brings a gripping perspective to these historical standoffs. Each narrative strand weaves a rich tapestry of the struggles and strategies that defined the wild, untamed West, making this episode a must-listen for anyone fascinated by the era where legends were forged on the frontier.

Podcasts we love

Check out these other fine podcasts recommended by us, not an algorithm.