Wild West Podcast

Welcome to the Wild West podcast, where fact and legend merge. We present the true accounts of individuals who settled in towns built out of hunger for money, regulated by fast guns, who walked on both sides of the law, patrolling, investing in, and regulating the brothels, saloons, and gambling houses. These are stories of the men who made the history of the Old West come alive - bringing with them the birth of legends, brought to order by a six-gun and laid to rest with their boots on. Join us as we take you back in history to the legends of the Wild West. You can support our show by subscribing to Exclusive access to premium content at Wild West Podcast + https://www.buzzsprout.com/64094/subscribe or just buy us a cup of coffee at https://buymeacoffee.com/wildwestpodcast

Wild West Podcast

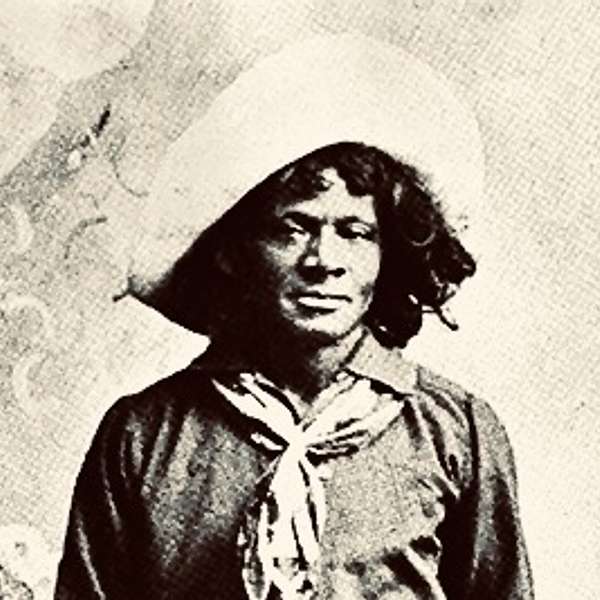

The Untold Legacy of Black American Cowboys: Nat Love's Journey and the Rise of the Western Trailblazers

Discover the unsung heroes of the Wild West as we share the riveting tales of Black American Cowboys, who emerged as skilled drovers and cow punchers in the post-Civil War era. Our journey through history celebrates these trailblazers, whose stories are often overshadowed, despite making up one-quarter of the 19th-century cowboy population. Join us for an episode that promises to enrich your understanding of these men who found autonomy and respect on the open range and left an indelible mark on the cattle industry.

We breathe life into the adventures of the legendary cowboy Nat Love, and travel the demanding paths that led to Montana, exploring the rich tapestry of experiences these cowboys faced. From the hardworking ranch hand to the multilingual trail cook, the episode paints a vivid picture of their indispensable contributions and the resilience they embodied. Saddle up with us as we pay homage to the courage, skill, and spirit of the Black American Cowboys, and celebrate their central role in the story of the American West. Join us at The Western Cattle Trail Association for 150 years of stories.

Black History is American History and February provides an opportunity to examine and reflect on Black American Cowboys' role in shaping the United States. In this episode we'll explore the Black Cowboys in the American West. We will examine their roles as ranch hands before and after the Civil War. Like all ranch hands and riders, african American Cowboys lived hard, dangerous lives. But Black Drovers were expected to do the roughest, most dangerous work and to do it without complaint. They faced discrimination out west, albeit less than in the South, which many had left in search of autonomy and freedom. As Cowboys they could escape the atrocious violence visited on African Americans in many southern communities and northern cities. We will recount the history of Black Cowhands along the trails in the early 1800s and some of their life experiences as drovers, cow punchers and trailblazers of the American West. In conjunction with the Western Cattle Trail Association, wild West Podcast proudly presents the history of African American Cowboys. When we portray a cowboy from the late 1800s, most of us probably consider a young man, occasion, tough, hardworking, ready for some amusement when the drive stops near a town. That description is accurate to a point, but we also need to consider that Black Cowboys likely constituted about a quarter of the working Cowboys in the 19th century. Historians tell us that of an estimated 35,000 Cowboys on the Western American frontier during the second half of the 19th century, probably several thousand were Black. In fact, the term Cowboy has its own rousing origins. Initially, white Cowboys were called Cowhands and African Americans were contemptuously referred to as Cowboys. African American men being called Boy regardless of their age stems from slavery in the plantation era in the South.

Speaker 1:The earliest evidence of African Americans as cattle herders, cowboys in North America can be traced back to colonial South Carolina, where stock grazers from Senegal and West Africa were brought explicitly to that colony. Because of their unique skills, they were brought to Spanish American colonies from Mexico to Argentina for similar reasons. Over the decades, the cattle industry and enslaved Africans who worked as Cowhands relocated across the South and reached Texas by the 1850s. Texas with one-third of the state's population comprising enslaved workers. African Americans were the majority of Cowboys in Texas in the early 1850s. Enslaved Cowboys were tasked with catching and tending wild cattle in the Gulf Coast brush country, working with Vicaros who migrated north from Mexico. These herders often drove long trains of steers led by oxen and trailed by bane dogs. A Smithsoniancom article called the Lesser Known History of African American Cowboys by Kate Najem Badim says 1 in 4 cowboys were black.

Speaker 1:When Americans began to settle in Texas, which was owned by Mexico in the early 1800s, many brought slaves with them. Najem Badim says by 1825, slaves accounted for 25% of the Texas settler population. During the Civil War, when white Texan landowners joined up to fight, slaves were left to care for their land and cattle. After the Civil War, blacks in Texas were freed but not well off. Most of them were illiterate, unskilled farmhands. Some were skilled artisans, others capable cowboys. These capable black cowboys' skill at managing cattle became much in demand by cattlemen who wanted to drive their livestock to northern markets.

Speaker 1:Hector Basie, a formerly enslaved ranch hand who was emancipated at 14, wrote about his life on the western frontier in his 1910 memoir the Negro Cowboy. A portion of his 34-page manuscript is reenacted in a moving portrayal by actor Eugene Lee, describing the dangerous but exhilarating work of the cattle trails. Here's an excerpt from the manuscript. After I was released from slavery I went to Harris County. There I commenced the cowboy life in earnest. In babyhood days the call of the winds and the wild-eyed cattle appeared to me. I seemed to understand them as no one else, even though they looked wild to others, they looked docile and tame to me. They were my silent friends and I loved to be with them. That made me take up the life I've led. Probably more than anything else, I loved to drive cattle on the open plains and to ride the worst buckin' bronc that could be found.

Speaker 1:In the early days Houston was quite a cattle market. Often times I drove cattle to this market. In those days a cowboy did not have a dozen different mounts, but lucky if he had two horses and a pack mule. In that time horses were hard to get that one could handle to do the business. The cowboy who had more to eat than hard-tackin' bacon was fortunate. We usually camped just where sunset found us and cooked our meat over a fire on a forked stick, and sometimes we had to eat at raw when we were short-handed or had signs of thieves or Indians. Both infested that part of Texas at that time and either was mean enough to do anything.

Speaker 1:According to the book the Negro Cowboys by Philip Durham and Everett L Jones, more than 5,000 Negro Cowboys joined the roundups and served on the ranch crews in the Cattlemen years of the West, attracted by the open range, the chance for regular wages and the opportunity to start new lives. They made significant contributions to the transformation of the West. The everyday life of all cowboys on the job was usually harsh, regardless of a cowboy's racial or ethnic background. Black cowboys were typically assigned horses with wild behaviors. They had to train them to be ridden. Typically, african-american cowboys had more than one duty. For example, a black cowboy who was a trail cook would be expected to be cook, hunt deer and wild turkey and perform on the trail by singing or playing a musical instrument. Some black cowboys also fulfilled the function of nurses, bodyguards and money transporters for a white cattleman. Although those freed slaves faced discrimination in many towns, they were well respected by the crew members they worked with on the trail.

Speaker 1:The West was a vast open space and a dangerous place to be. Cowboys had to depend on one another. They couldn't stop in the middle of some crisis, like a stampede or an attack by wrestlers, and sort out who's black and who's white. Black people operated on a level of equality with the white cowboys. Individually, several black cowboys deserved to have their stories told. One is Nat Love, who first comes to mind among the many African-American cowboys who stand out among the many others. Even though most historians declare the story of Nat Love as mostly fantasized, he is worth telling, for he became one of the most noted black cowboys who helped shape the West during his career. The following narrative is based on a book by Nat Love entitled the Life and Adventures of Nat Love, better known in the cattle country as Deadwood Dick.

Speaker 1:Nat was born into slavery in 1854 on Robert Love's plantation in Davidson County, tennessee. Nat Love's father, samson Love, and his mother, whose name has been lost over the years, were slaves held by Robert Love of Davidson County, tennessee. Like most slaves, they assumed the last name of their master. Raised in a log cabin, nat's father had become a slave foreman on the plantation and his mother toiled in the kitchen of the big house. Nat was looked after primarily by an older sister when he was young, but she, like her mother, had tasks in the kitchen, so Nat effectively looked after himself. While most enslaved people were illiterate, nat received no conventional education but with the help from his father he learned to read and write. Nate writes in his autobiography about his early life on Robert Love's plantation In an old log cabin on my master's plantation in Davidson County in Tennessee in June 1854 I first saw the light of day.

Speaker 1:The exact date of my birth I never knew, because in those days no count was kept of such trivial matters as the birth of a slave baby. They were born and died, and the account was balanced in the gains and losses of the master's chattels, and one more or less did not matter one way or the other. My father and mother were owned by Robert Love, an extensive planter and the owner of many slaves. He was, in his way and in comparison with many other slave owners of those days, a kind and indulgent master. My father was a sort of foreman of the slaves on the plantation and my mother presided over the kitchen at the big house and my master's table, and among her other duties were to milk the cows and run the loom, weaving clothing for the other slaves. This lent a scant time to look after me, so I early acquired the habit of looking out for myself. The other members of father's family were my sister Sally, about eight years old, and my brother Jordan, about five. My sister Sally was supposed to look after me when my mother was otherwise occupied, but between my sister's duties of helping mother and chasing the flies from master's table, I received very little looking after from any of my family. No necessity compelled me at an early age to look after myself and rustle my own grub.

Speaker 1:After the Civil War, when the enslaved people were freed, nat's father worked a small farm he rented from his former master, robert Love, but freedom was short-lived for the previously enslaved person, as he died just a few years later. Nat then took assorted jobs on area plantations to help to sane the family and found that he had extraordinary skill in breaking horses. In February of 1869 he left Tennessee with $50 he received from breaking colts and the sale of a horse and headed west for Kansas Territory. Nat writes the following about leaving home it was on the 10th day of February 1869 that I left the old home near Nashville, tennessee. I was about at that time 15 years old and though while young in years and hard work and farm life had made me as strong and hearty much beyond my years and I had full confidence in myself as being able to take care of myself and making my way, I wanted to see more of the world, and I began to realize that there was so much more of the world than what I had seen. The desire to go grew on me from day to day. It was in the west and it was the great west that I wanted to see.

Speaker 1:Nat must have taken on various jobs before reaching Dodge City, for the Santa Fe Railroad did not arrive in Dodge City until September of 1872 and the cattle season did not open until 1875. According to Nat's biography, he states that on his way to southwest Kansas he walked hitched rides and eventually worked his way to Dodge City. Additionally, nat claims he was looking for work on a ranch near the new town of Dodge City. Their love met up with a Texas cattle company that had just delivered a herd and was preparing to head back. From a historical account of the first ranch established in the area, nat may have wondered onto some of the Saudis and dugouts near an abandoned ranch complex at the Cimarron Crossing, a crossing station previously owned by Robert Wright. This would have placed Nat in the area much later than 1869. According to historical journals, the only cattle establishment in the area of Dodge City was located about 12 miles west of Fort Dodge.

Speaker 1:The story of the first cattle drive and ranch established is told by Doc Barton during the summer of 1872 from an interview by Tom Stout of Dodge City, kansas. They started north from Burnett County, texas, with 3,000 head of Longhorn Texas cattle. This trail outfit consisted of 12 men and they were some three months on the trail before they reached Finney County, kansas, where Garden City is now located. They held the herd for some three months in the Garden City territory and worked down the R Kansas toward now Ingalls located. That was before the railroad reached Dodge City. Although much of the railroad grade was partly completed to what is now the west line of Kansas, large crews were working on the grade and a ready market was found for the cattle. When they reached what is now Ingalls, kansas, they found a large corral still standing on the river flats just east of where the present Ingalls Bridge now crosses. There were also the remains of Saudis and Dugouts as well as the remains of a few Dobies on the river bottom just north of the corral. For there was a regular campground of the old Santa Fe Trail which crossed the R Kansas River at what is known as the Cimarron Crossing of the R Kansas.

Speaker 1:Nats Book shows that the cowboys were having breakfast when he joined them. He had no proper trail gear or guns and looked more like a farmer than a cow puncher, the never shy Nats, approached the trail boss and asked for a job. The boss agreed that Nats could join them if he could break a horse named Good Eye. The boss told him if you can ride him I'll hire you. If you can't, then there won't be no job for you. Nats' account said he rode the horse until it tired out. When he dismounted, the boss hired him at $30 a month through the Duval Ranch, took him to town and bought him complete new trail gear, including a fine 45 Colt Revolver. That would later say it was the most challenging ride he'd ever had.

Speaker 1:After leaving Dodge City with 15 hardy, experienced riders, all except himself were among a jolly set of fellows. They were ready for anything that might turn up along the trail for home. Then, only a few miles outside of Dodge City along the lonesome trail, the small band of cowboys encountered the Victoria tribe of Indians and had a sharp fight. That writes about his first Indian fight experience in the following narrative these Indians were nearly always harassing travelers and traders and the stock men of that part of the country and were very troublesome. In this band we encountered about a hundred painted bucks, all well-mounted. When we saw the Indians, they were coming after us, yelling like demons. As we were not expecting Indians at this particular time, we were taken somewhat by surprise. We only had 15 men in our outfit, but nothing daunted us. We stood our ground and fought the Indians to a stand. One of the boys was shot off his horse and killed near me. The Indians got his horse, bridal and saddle. During this fight we lost all but six of our horses, our entire pack and outfit and our extra saddle horses, which the Indians stampeded, then rounded them up after the fight and drove them off. As we only had six horses left us, we were unable to follow them, although we had the satisfaction of knowing we had made several good Indians out of bad ones.

Speaker 1:This was my first Indian fight and likewise the first Indians I had ever seen. When I saw them coming after us and heard their blood curdle in the ale, I lost all courage and thought my time had come to die. I was too badly scared to run. Some of the boys told me to use my gun and shoot for all I was worth Now. I had just got my outfit and had never shot off a gun in my life, but their words brought me back to earth and seeing they were all using their guns in a way that showed they were used to it, I unlimbered my artillery and after the first shot I lost all fear and fought like a veteran. We soon routed the Indians and they left, taking with them nearly all we had, and we were powerless to pursue them. We were compelled to finish our journey home almost on foot, as there were only six horses left to fourteen of us. Our friend and companion, who was shot in the fight, we buried on the plains, wrapped in his blanket and stones piled over his grave. After this engagement with the Indians I seemed to lose all sense of what fear was, and thereafter, during my whole life on the range, I never experienced the least feeling of fear, no matter how trying the ordeal or how desperate my position.

Speaker 1:The sixteen or seventeen year old must have quickly adjusted to the life of a cowboy, demonstrating exceptional skills as a ranch hand and practiced so often with a 45 revolver that his shooting skills also became notable. After three years with the Duval outfit, love pushed on to Arizona when he began working in 1872 for the Gallinger Ranch on the Healer River. He traversed many major western trails there, sometimes working in dangerous circumstances in Indian battles and clashing with wrestlers and bandits. During these years, as an Arizona cowboy, nat was referred to as Red River Dick and claimed to have met many famous men of the west, including Pat Garrett, bat Masterson and Billy the Kid. Gaining a reputation as one of the best all around cowboys in the Duval outfit, he soon became a buyer and their chief brand reader. He was sent to Mexico several times in this capacity and soon learned to communicate to fluent Spanish. That conveys his thoughts on his employment ventures working for the Duval outfit in the following narrative.

Speaker 1:Having now fairly begun my life as a cowboy, I was fast learning the many ins and outs of the business, while my many Romans over the range country gave me a knowledge of it not possessed by many at that time. Being of a naturally observant disposition, I noticed many things to which others attached no significance. This quality of observance proved of incalculable benefit to me in many ways. During my life as a range rider in the western country, my employment with the Pete Gallinger company took me all over the panhandle country, texas, arizona and New Mexico with herds of horses and cattle from market and to be delivered to other ranch owners and large cattle breeders. Naturally, I became very well acquainted with all the many different trails in grazing ranges located in the stretch of country between the north of Montana and the Gulf of Mexico and between the Missouri state line and the Pacific Ocean. This whole territory I have covered many times in the saddle, sometimes at the rate of 80 or 100 miles a day. These long rides and much traveling over the country were of great benefit to me, as it enabled me to meet so many different people connected with the cattle business and also to learn the different trails and lay of the country generally. Among the other things that I picked up on my wanderings was the knowledge of the Spanish language, which I learned to speak like a native. I also became very well acquainted with the many different brands scattered over this stretch of country. Consequently, it was not long before the cattlemen began to recognize my worth and the Gallinger company made me their chief cattle brand reader, which duties I performed for several years with honor to myself and satisfaction of my employers In the cattle country. All the large cattle razors had their squad of brand readers, whose duty it was to attend all the big roundups and cuttings throughout the country and to pick out their own brands and to see that the different brands were not altered or counterfeited. They also had to look at the branding of the young stock.

Speaker 1:In the spring of 1876, the Gallinger Cowboys were sent to deliver a herd of 3,000 steers to Deadwood, south Dakota. When the crew arrived on July 3, the citizens were busy preparing for a 4th of July extravaganza. One of the many organized events during the celebration included a cowboy competition with a $200 cash prize to the winner. During the tournament, nate soothed, saddled and mounted a wild horse in a record 9 minutes compared to 12 minutes for the next contender. He also won the sharpshooting contest.

Speaker 1:He competed with other competitors in roping, bridling, saddling and shooting, winning every contest. Nat walked away with a $200 prize and the nickname of Deadwood Dick. Love retired in 1890. In 1907, nat Love published his autobiography, the Life and Adventures of Nat Love, better known in cattle country as Deadwood Dick, a tale that tended to take on the epic proportions more noted in the many dime novels of the time. Though he boasts in the book that everything happened, there is little external verification, such as those famous Western men that love allegedly met, even though most historians believe many of the details in the book are inflated, but even so he lived an adventurous life.

Speaker 3:Brad, it's important to note that in that love story he states he left home in 1869 and arrived at Dodge City shortly after. As most historians would have read Love's book come to the conclusion, some of the text within the book is exaggerated. So today I would like to excerpt some history about Dodge City between the years of 1870 and 1872. Brad, what was in the area between 1870 and 1872? According to your knowledge of Dodge City?

Speaker 1:Well, mike, there was already actually quite a lot going on in the area.

Speaker 1:Certainly, fort Dodge was the major military post in the area, so you had the soldiers who were stationed there traversing the plains.

Speaker 1:The fort itself had already become a major hub for the Buffalo trade, so you had plenty of Buffalo hunters coming in and out and we've got stories of their scuffles with the soldiers and the Buffalo industry was exploding already by this point the Santa Fe Trail was still very active as the railroad had yet to be laid. So there were various camps along the area, certainly as you got out to the Cimarron Crossing area. So the area between Fort and the Cimarron Crossing was quite a hub of activity, just as freighters, soldiers, scouts were traversing the area. And then also you had the railroad was already planning its route through the area. You had railroad scouts, also their military companions, on their way out through there scouting the route for the coming railroad. And by 1871, henry Sittler became one of the first permanent settlers in the area of, very specifically, what is now Dodge City with his small ranch cattle operation and everything that went on there. So it was very much a hub of activity even prior to the actual establishment of Dodge City proper.

Speaker 3:Another question that comes to mind after reading Love's book is how he writes about his first experience with Indian fighting. Returning to Texas, they would have crossed over the south side of the Arkansas River, Brad, in early 1800s. What existed on the south side of the river and what? The Native American Indians have been hostile to travelers in the area?

Speaker 1:Well, by and large what existed on the south side of the river was exactly the same thing that existed on the north side A lot of great Buffalo country. The Buffalo industry itself was active on both sides. Politically speaking, however, the river was the boundary line for the Medicine Lodge Peace Treaty, in that white hunters were legally not allowed to hunt south of the river. So south was, strictly speaking, indian country, and Indian country only. It wasn't until the early 1870s really, where it became blatant that white hunters were heading south of the river because that's where the big herds were. As a result of the Medicine Lodge Peace Treaty, the hunters north of the river had pretty much wiped out most of the Buffalo herd. So south of the river, in Indian country, that's where the Buffalo were meaning, that's where the money was. So they started heading south of there too. But dominantly south of the river was Indian country, buffalo country, that white hunters were not allowed in.

Speaker 3:Brad, in conclusion, how would you sum up Nat Love's life as a drover and his contributions to expanding the West?

Speaker 1:The narrative about Nat Love tells of the grandeur of the West in a more extensive cultural arena. As the West was settled and assembled, the exploits of this individual became a legend In grand. Narratives about him were handed down to many a campfire. Over time, though, his legend has been overlooked. Now, this juncture of time, we celebrate Black History Month and recall again the contributions of this courageous and heroic African American. Nat Love was indeed an American hero, and we hope you have enjoyed his story. So join us again on February 21st as we take you back in the history of another great African American cowboy named Boes Izard. This and the story of the Western Cattle Trail can be found at westerncattletrailassociationcom slash blog.

Speaker 2:I ride in old pain. I lead in old land. I'm off for Montana for to throw the hula. They fade in the coolies. They water in the draw. The tails are all matted and their backs are all raw. Ride around, little loogie. Ride around real slow. The fiery and snuffy are raring to go. Goodbye old pain, I'm leaving shine. Goodbye old pain, I'm off for Montana. My foot's in the stirrup, my pony won't stand. Goodbye old pain, I'm leaving shine.

Podcasts we love

Check out these other fine podcasts recommended by us, not an algorithm.